Art in Conversation with Pettik Leó Zakariás

If you're in London and looking for a good time, look no further than Big Squeeze Soul, a vinyl prodigy duo filling pubs and clubs with roaring soul classics and insatiable energy. This group had me dancing my ass off in a sweaty, illegal basement bar, early-morning South London—after my friends and I swore we were only going out for a few drinks.

That’s how I met Leo. I had just left the dancefloor to satisfy my thirst for another cider when he gifted me a rose. "For your dancing," he said. I replied, "It's not me, it's the music!" It made my night. I lost the rose later but made sure to pluck a few petals to press in my notebook.

At the top of the next hour, Leo and I had our final encounter of the night. I stumbled upon him in the black light room, sketching. In my drunken enthusiasm, and still charmed by the earlier gift, I interrupted him to ask if he was an artist. I clumsily explained that I run a small art collective and asked if I could interview him. I don’t remember what happened next, but the following day, I found one of his prints folded small at the bottom of my purse. It was incredible — during a late breakfast, my flatmates and I fawned over its texture and elemental depth. It had his Instagram handle neatly tucked into the bottom left corner. I think he had agreed.

Miraculously, we both kept our word. A few weeks later, when he returned to London to see a friend, this conversation occurred at a coffee shop immediately upon his arrival:

________________________________

Pettik Leó Zakariás @qllliiilllp on Instagram, studying at the University for Creative Arts Budapest/Bristol

________________________________

Kisi: You mentioned you're studying digital art. I’m interested in your technique because from what I’ve seen, your work is really diverse. It almost looks like there are elements of traditional art mixed with digital. I’d love to hear about your approach to the work you’ve done so far and how long you’ve been in university, that sort of thing.

Leo: I’ll talk about my work first. The basis of my work is painting—mostly traditional painting, particularly acrylic. I used to do a lot of photo collage, and then I started collaging from my paintings. Eventually, I moved on to doing collages in Photoshop because it's easier; I don’t have to print things out repeatedly. I really got into the intricacies of Photoshop. It’s a fun software, almost like a game—very interactive with lots of functions that can be used for things other than their intended purpose. That's what I enjoy the most right now. At university, I’ve done a range of things, but I often return to collaging in Photoshop.

Kisi: I do collage work too, but I like to scan elements in real life and bring them into Photoshop, then go crazy with them. I’m an amateur at Photoshop, so it’s fun to mess around and figure out new things. But your work is incredible. The piece you gave me was black and white, and I love that, but on Instagram, I noticed you use a lot of color. How do you interpret your work, and where does it come from? What inspires it? Is it a pastime, a necessity in your life, or something else?

Leo: That’s an interesting question. First of all, exploring Photoshop is the most fun part, so I think you’re in a great spot. I’ve had formal art education since I was young, but I never had formal Photoshop education. I practiced by myself. Not having formal instruction isn’t much of a barrier if you’re enjoying it. I spent hours using it as a teenager, and the internet is full of tutorials. Between that and my practice, I’ve developed a solid grasp on certain things—though there are still parts of Photoshop I don’t understand because it’s so vast.

As for my education, I’m not sure if Photoshop will be something I can use in a future job. It’s more of a passion for me. I’ve sold some prints and had a few commissions for posters, but I don’t know how realistic it is to make a career out of it.

Kisi: So you’re working on other things as well, but are you also trying to bring your fine art to a larger audience? You recently had an exhibition. Was that work mainly painting, or was it a mix with Photoshop?

Leo: Let me show you what I made. I’m lucky because my family is very supportive of my art interests, which is definitely a blessing. I wanted to do more interactive digital art, like 3D modeling and coding in Unity, which is game design software. I’ve done a few things in that direction and wanted to take it into virtual reality. My family got me a VR headset, and I created a piece for it, which was exhibited. However, now that I’ve worked with VR, I’m not as fond of it. It feels monopolized by big tech companies, and the whole process is frustrating. For example, to transfer what I made in Unity to the VR headset, I needed a specific verified Facebook account, which required me to submit government ID. I found that unsettling. Regarding my education, I’m heading into more tech-heavy areas, but I’m increasingly concerned about the materials used in computers and how unethical some of those practices are.

Kisi: There’s a lot of moral ambiguity in the art world right now. Art, as a practice, seems antithetical to the systems that the world abides by—money, status, recognition. Artists aren’t typically in it for those reasons. But now, you need to market yourself on social media, fit your work into certain formats, and get exhibitions, which often depend on things like the status of your university or connections. It feels like you have to compromise your integrity. When you mentioned VR, it made me think about how surveillance and digital footprints are such big issues. It’s both liberating and unsettling, as technology can be used for good or evil. I’d love to hear more about your exhibition and the process of creating in virtual reality. What were the moral questions you encountered during that process?

Leo: Well, technology itself isn’t inherently evil, but it’s often developed by people who prioritize profit over human life. That’s true for the materials used in computers too. The sourcing of those materials exploits people, sometimes to the point of death. Morally speaking, that’s a major issue with digital art. Every time you upgrade your computer to render things faster, you’re supporting these unethical business practices. I try to keep my equipment for as long as possible because upgrading constantly is not only expensive but also wasteful. Marketing pushes us to always have the latest and greatest, which I find toxic. That’s the moral conundrum of it all.

Kisi: It’s hard to reconcile that tension. I love that you’re mindful of it. And speaking of your exhibition, how was it? Where did the opportunity come from, and how did it feel once it was over?

Leo: The opportunity came through my university. I’m in my third year, though I’m going to repeat it because I haven’t done my dissertation yet. This was our graduate show, my peers are graduating. The leader of our course is connected to an organization called ISEA (International Symposium of Electronic Art), which is a big digital art festival. They sponsored our exhibition, allowing us to get a great venue in Peckham, London. The venue, Safe House, is an old, crumbling house, which is very different from the sterile white spaces usually used for exhibitions. It’s full of holes and has a very raw, corroded aesthetic, which worked beautifully with the art.

Setting up was fun—I got to hang out with friends. But the opening night was overwhelming. So many people showed up, including my friend who traveled two hours within London just to be there. It was more of a social event than a networking one, and I felt a bit out of place as the exhibiting artist.

Kisi: I can imagine how intense that must have been. Networking is its own kind of art. It sounds like the exhibition had a great community feel, though, which is so important in art.

Leo: Yes, community is crucial. Art is better when we share ideas and help each other out. There was a lot of collaboration between the artists for this exhibition. I helped several friends with their projects, like filming and gathering props. We even went dumpster diving to find materials for one friend’s dystopia-themed film. We found a board game about endangered species or something, and it had a bunch of pictures of animals printed on it. Now that I’m describing it, it sounds mundane, but at the time, it was like a mystery box. You pull it out of the dumpster, and it’s this board with animals printed on it and a big, funky label saying “Endangered Species: The Board Game.” It was just like, "What the fuck is this?" Anyway, sorry, that was a tangent. It was a lot of fun and incredibly inspiring to work together like that.

Kisi: No, it’s fine. I needed that for context.

Leo: Yeah, and it goes back to the community. Doing things in a community really elevates the experience. Wow, that sounds pretentious.

Kisi: But it’s true. Sometimes the truest things can sound pretentious. We don’t exist in a vacuum. People like to say, “I did it all on my own,” but the reality is no one does anything alone. When people get famous, they might say, “Nobody helped me,” but they had a team of people—30 or more—doing their promotion, setting up their stage, checking the audio, making sure the lighting works. No one is truly alone, and I think that's something people tend to forget.

Humans, as individuals, aren’t better than other animals in most ways. We aren’t the fastest, we aren’t the strongest, and our bodies are actually quite fragile. But what sets us apart is our ability to organize and communicate. We’ve evolved to collaborate on complex tasks. Sure, other animals have organizational structures too, but our level of communication and planning is what makes us exceptional. That’s something I want to bring back to younger generations—this idea that community is more important than individualism. It’s hard for young people to grasp that sometimes, but it’s crucial.

I agree that everything is better in community, and it's important for young people to understand that. I live in an artist house in New York with seven other people. We all make art—not necessarily in direct relation to the collective—but we all contribute in some way. For example, some of the musicians in the house play at our events, one person does fashion design and I interviewed him for a project, and another does graffiti art and has designed posters and graphics for us. We all collaborate artistically, but we also learn to work together in everyday ways—cleaning, cooking, and maintaining the space. There’s inherent creativity in those actions too.

I think a lot of young people are content with their work just living online because that's where it gets the most attention. But I’m curious how you feel about having both an online presence and physical exhibitions. Do you value one over the other? What satisfies you more? When you create, do you think about how your work will look online, or are you more focused on how it will be received in person? Where do you hope your art will go? Throw in a crazy dream—what's the big vision?

Leo: First of all, the internet is a fascinating space, and it ties back to what we were saying about collaboration. What’s exceptional about humans is our ability to communicate and preserve history. The internet is an extension of that—it’s this non-physical but expansive space. I often mythologize it for myself because it feels so absurd in its own way.

When I post my art, mostly on Instagram right now, I think about the formatting, but I’m not trying to become an art influencer. For me, it’s more about sharing with friends and other artists I admire. In the future, I’d love to have my own website. Living in an artist house, like you mentioned, must be amazing. I’ve lived with artists for two years, but we’ve never collaborated as deeply as being part of a collective. I think artist collectives are incredibly powerful for creation.

Professionally, I’d like to go into organizing art spaces—collectives, exhibitions, that kind of thing. Everyone has different skills, and nobody makes it alone. Unfortunately, when some artists get famous, they start exploiting those around them. I definitely don’t want that. I’d much rather be in a collective, collaborating and sharing with others, rather than building fame for myself.

It all ties back to living together. You mentioned cooking—it’s one of the most important cultural institutions, stretching back to the beginning of human history. Cooking together or for others makes it more meaningful. When I’m cooking for myself, I’ll throw something together, but when it’s for others, it becomes an event. It’s the same with art—it’s better when it’s shared.

Kisi: That’s a really powerful thought. I think that sense of community is hard for a lot of young people to grasp because they’ve been conditioned to think that individualism is the key to success. But in reality, you’re always giving more than you get, whether you’re working within a community or within capitalism. It’s just that capitalism gives the illusion of getting more back because of money, but you're still being exploited. In a community, the giving feels more tangible, more human.

That idea—that we’re always giving more than we get—is something I’ve been grappling with in New York. I started a collective in high school, and now we operate in four cities across the U.S. But I often feel like people see it as a place to get opportunities, not to contribute. I’ve had a bit of a crisis over it, and that’s part of why I came to London—to meet artists who truly understand the purpose of community.

But back to your work—I’m really intrigued by what you said earlier about the absurdity of existence. Your work feels like a blend of dystopian and raw, with this futuristic, tech-driven energy. I’d love to know how you define your own work. What do you want people to take away from it, and how do you see your own creative process?

Leo: Labeling my work has always been tricky. For a long time, I didn’t know what to call it. Right now, I have a folder on my computer where I save most of my work, and I’ve labeled it “Mystic Sci-Fi”—mystical science fiction. That title has stuck with me because it fits the imaginative, narrative-driven nature of my work.

When I create, I often invent narratives in my head. These aren’t fixed stories—they evolve as I work. The narrative changes from the beginning to the end of the piece, and sometimes it’s forgotten altogether. But that’s part of the process. It’s the flow state I get into when I’m really invested. That’s why I love collage and digital work—because I can keep editing and rearranging. With painting, it’s harder to make those adjustments.

Surrealism has also been a big influence on my work, especially when I was younger. There’s a lot of narrative energy in what I create, and I think that comes across in the pieces I’ve brought today.

Kisi: I’m excited to see them. Let’s dive into these pieces.

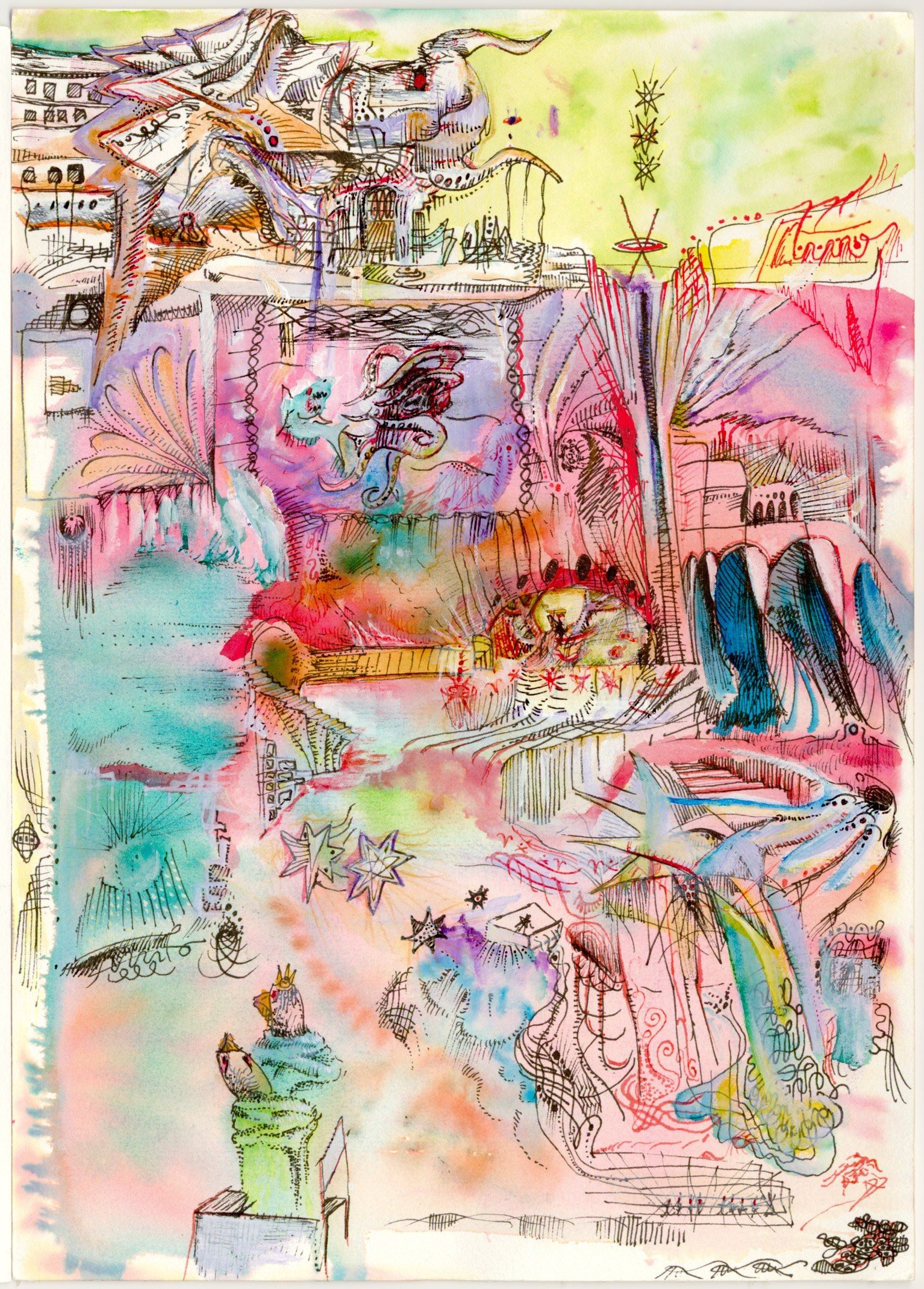

Leo: Yeah, the more you look at it, the more stuff you see, especially with this one. This one, more so than the others, usually works best with traditional art. It’s mostly watercolor and inks that I scanned, refined, and digitized to be in that black-and-white printed format. Both pieces have narratives, but one has a more developed narrative. I can recount something for you if you’d like.

Kisi: That’s what I was thinking. These three stand out to me. I assume all of them have narratives, but these seem to suggest a deeper backstory or context. But of course, if you don’t feel like diving into them, I can just get scans of the pieces and let people interpret them for themselves.

Leo: It’s valuable feedback to hear that these three stand out—cool to know! Other people have pointed out these three as well, which is interesting. The one with the most narrative behind it is this one, the one with the blue background. The narrative isn’t a traditional story, but more of a world-building exercise. The idea is a kind of demonic realm—not hell, not in a religious sense, but a separate dimension.

In this universe, there are wizards, which is a standard feature in my work. These wizards summon what I call demons, though they aren’t demonic in the traditional sense. The term "demon" is just evocative for me. The wizards summon these demons by using a metaphysical star—a star that emits a sort of metaphysical radiation. It’s not like gamma rays, but something similar, some kind of energy. If you have the right kind of lens, which in this case is a mystical glass lens, you can focus the light onto a mystical artifact and imbue it with a soul. That’s how the demons are summoned.

So, this figure is wearing a suit of armor because it was once just a suit of armor, but the star’s energy brought it to life. The demons are summoned, given a task, and once they complete it, they’re discarded. The wizards think they're simply summoning and using these demons, but in reality, they’re doing much more harm than they realize.

The lens they use is provided by a figure inspired by Satan, though not in the traditional sense of an all-powerful evil being. This entity oversees the dimension where the demons reside. The wizards think they’re just casting a spell, but in reality, they’re signing a contract with this entity. Once the demon finishes its task, the entity takes the demon back to its realm, building an army for its own purposes. Eventually, the entity plans to return to the human realm with this army, though I haven’t fully fleshed out its motivations yet.

In this world, it’s structured like an inside-out planet. Imagine if the universe were a solid material, and there was a hollow sphere of air in the center. The palace where this entity resides is located at the core of this inside-out planet. Once the demons complete their tasks, they’re transported to the palace, which is non-Euclidean and ever-changing—a labyrinth you can’t navigate out of. The surface of this world is made up of deserts and rainforests, though the rainforests aren’t exactly plants.

The demons can fight each other, and if they cut off another’s limb, they can attach it to themselves. Over time, demons can heal, but their wounds turn into gray, bony material. Eventually, demons who have lost too much of themselves become immobile, rooted into the ground, and they form the trees in the landscape. It’s a cycle of destruction and transformation.

Kisi: I love how it ties into your themes of erosion and things coming and going, as well as the idea of exploitation.

Leo: Exactly. The wizards are exploiting these beings, but they’re unaware of the full extent of the harm they’re causing. Meanwhile, the demonic entity is amassing power. It’s a layered world, with so much to explore. The background of the piece, by the way, is actually based on an image of a kelp forest—those beautiful underwater habitats for sea otters and seals. They’re endangered now, which is tragic. I love the natural world, and marine biology has always been a huge influence on me.

Kisi: Kelp forests are so amazing! I’ve snorkeled in one before—it’s an otherworldly experience. Now that you mention it, I can see that influence in the background. It gives the piece such depth.

Leo: I’m jealous! It must have been incredible. I wanted to bring that sense of a mystical, yet very real, natural world into this piece. The face of the demon is based on an insect, tying the natural and mystical elements together. It’s a suit of armor, but it’s also alive, with this insect-like, otherworldly face. That’s what I was thinking about while I painted it, but once the piece is finished, I’m more interested in how other people interpret it. I have my own lore, sure, but I love hearing what others see in it.

Kisi: That’s so fascinating. I love the complexity and depth of the narrative. And now I see this one in a whole new light. It’s such a rich, imaginative space. Let’s move on to another piece—this one, with the intricate textures, caught my eye. It feels more abstract and less action-oriented than the first piece. Is there a solid narrative here, or is it more open to interpretation?

Leo: I’m curious to know what you see in this one before I tell you what I had in mind.

Kisi: Okay, well, I see it as a kind of take on a biblical angel, with the wing and the eye in the middle. The texture reminds me of graffiti, like something sprayed over a brick wall. There’s a sense of dystopian energy, but also a kind of gritty, grounded feel. It makes me think of an abandoned cathedral or some sort of spiritual experience in a post-apocalyptic desert. Maybe during an eclipse, something like an angel—though you’re not sure if it’s good or bad—descends. It feels like a tumbleweed blowing through a psychedelic dream.

Leo: Wow, that’s really spot-on! It’s not exactly the same narrative I had, but your interpretation fits perfectly. This one has less of a structured narrative, though. The desert landscape is actually formed from an image of a bear skull—the jawline here, and the eye sockets there—but that’s not what it has to be. I love that you saw it as something else.

The main element here is the sea angel, which is based on a real marine creature related to sea slugs. They’re small, bioluminescent creatures that float in the deep ocean. I’m fascinated by marine biology and deep-sea life, so I wanted to bring that alien, otherworldly quality into this piece. The composition plays with scale, reversing the usual order of things. The sea angel, which is tiny in real life, is this massive figure, while the bear skull forms the landscape, and the tower is a small detail in the background.

The texture comes from screen printing. I love the process because it introduces this natural, eroded pattern where the ink doesn’t always fill in evenly. After I scanned it in, I inverted the colors to create the final piece. It’s more about texture and composition than narrative, but I think the idea of a desert being a hallucinogenic, mystical place fits perfectly.

Kisi: The way you play with scale and texture is incredible. I love the juxtaposition of the intricate details. It really pulls you in. This one is my favorite by far—it’s so captivating.

Leo: Thank you! This piece is meant to be stared at for a long time, to reveal more details the longer you look at it. It’s about getting lost in the patterns, like a labyrinth. The narrative is looser, but I see it as a kind of cybernetic necromancy. These beings are not evil, but they repurpose human skeletons, adding machinery to create new life. They need only 37% of a skeleton to create one of themselves, attaching hydraulics and processors to the bones. They exist in a space between life and death, intelligence and machine.

Visually, I wanted this piece to be a labyrinth, something you can get lost in. The figures were originally created using an acetone transfer technique with images of dead fish, which I photographed myself. The process was experimental and fun—I even used tea instead of watercolor for some parts, to create that brownish hue. Then I scanned it, added digital details, and inverted it to create this final version. I love how it turned out.

Kisi: That’s so fascinating—your process is so rich and layered, from conceptualizing to the material production. You’re synthesizing so many different aesthetic aspects and that's tangible in the final result. It's been amazing to hear about your pieces. I’d love to stay in touch and hear more about your future projects. This work is so unique, and I’m excited to share it with others.